The combat myth is one of the most influential themes in ancient literature. The narrative depicts a cosmic battle between a heroic god and a monstrous enemy, often representing the forces of chaos and order. The combat myth has been found in various forms and variations across the ancient Near East, from Mesopotamia to Ugarit to Israel and Judah.

The combat myth also influenced the biblical tradition, especially in its portrayal of God and creation. In this article, we will explore the origins and development of the combat myth in the ancient Near East and examine how it shaped the biblical worldview.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

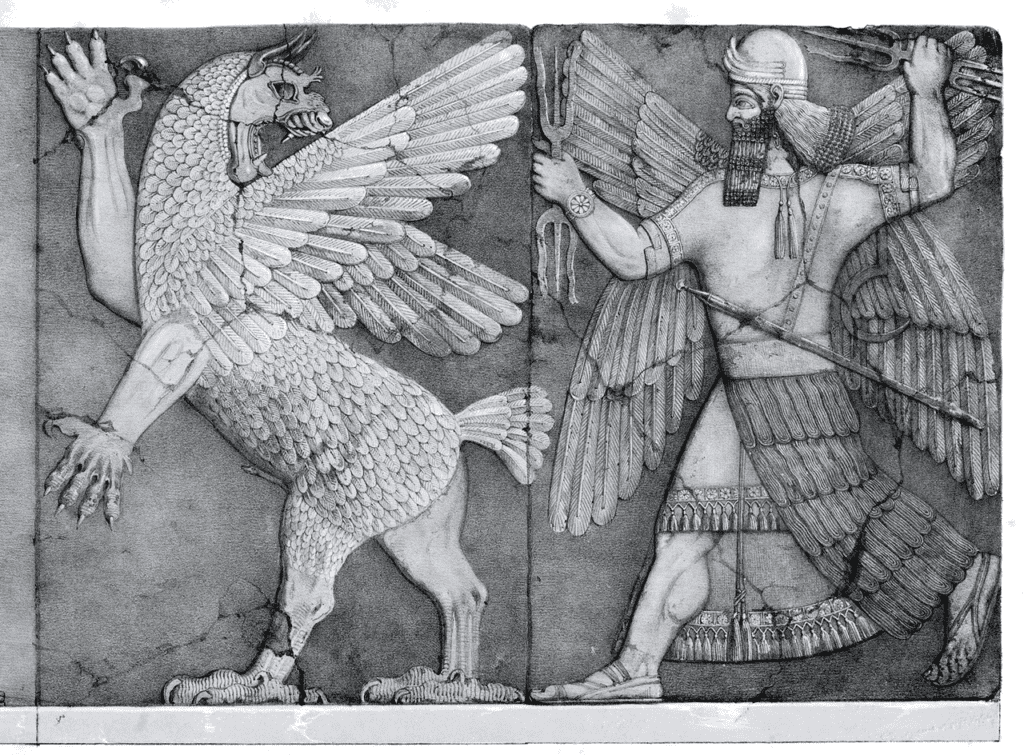

Ninurta vs Anzu

One of the earliest examples of the combat myth is the Sumerian-Akkadian epic of Ninurta and Anzu, dating back to the second millennium BCE. The story tells how Anzu, a giant bird-like creature, steals the Tablet of Destinies from Enlil, the supreme god of the Mesopotamian pantheon. The Tablet of Destinies contains the decrees that govern the cosmos and grant authority to the gods. With the Tablet in his possession, Anzu usurps Enlil’s power and threatens to overthrow the divine order.

Anzu often gazed at Duranki’s god, father of the gods,

– Anzu Tablet 1

And fixed his purpose, to usurp the Ellil-power.

‘I shall take the gods’ Tablet of Destinies for myself

And control the orders for all the gods,

And shall possess the throne and be master of rites!

I shall direct every one of the Igigi!’

He plotted opposition in his heart

And at the chamber’s entrance from which he often

gazed, he waited for the start of day.

While Elli! was bathing in the holy water,

Stripped and with his crown laid down on the throne,

He gained the Tablet of Destinies for himself,

Took away the Ellil-power. Rites were abandoned,

Anzu flew off and went into hiding.

Ninurta, the son and champion of Enlil, volunteers to fight Anzu and recover the Tablet. After a fierce battle, Ninurta defeats Anzu with his magical weapon, the Sharur, and returns the Tablet to Enlil. As a reward, Ninurta is praised as the king of the gods and given dominion over the mountains and their resources.

The epic of Ninurta and Anzu reflects the political and religious ideology of Mesopotamia, where kingship was seen as a divine gift and a cosmic responsibility. Ninurta represents the ideal king who protects his father’s throne and preserves the cosmic order. Anzu represents the forces of chaos and rebellion that threaten to disrupt the harmony of creation. The Tablet of Destinies symbolizes the source of legitimate authority and power that belongs to Enlil and his chosen successor. The epic also expresses the importance of wisdom, courage, and loyalty as virtues that enable Ninurta to overcome Anzu.

Marduk vs Tiamat

Another famous example of the combat myth is the Babylonian epic of Enuma Elish, composed in the first millennium BCE. The story tells how Marduk, the patron god of Babylon, rises to supremacy among the gods by defeating Tiamat, the primordial goddess of the sea. Tiamat is enraged by the younger gods who have killed her husband Apsu, the god of fresh water, and plots to destroy them. She creates an army of monsters and appoints Kingu, her new consort, as their leader. She also gives him the Tablet of Destinies as a sign of his authority. The other gods are terrified by Tiamat’s wrath and seek a champion who can face her. Marduk agrees to fight Tiamat on one condition: that he be recognized as the king of the gods if he wins. The gods accept his demand and entrust him with their fate.

Marduk confronts Tiamat in a cosmic battle that shakes heaven and earth. He uses his wind weapon to split her body in half and creates the sky and the earth from her remains. He also captures Kingu and takes back the Tablet of Destinies. He then organizes the cosmos according to his will and assigns roles and duties to each god. He also creates humans from Kingu’s blood to serve as his slaves and worshipers.

Face to face they came, Tiamat and Marduk, sage of the gods.

– Enuma Elish Tablet IV

They engaged in combat, they closed for battle.

The Lord spread bis net and made it encircle her,

To her face he dispatched the imhullu-wind, which had been behind:

Tiamat opened her mouth to swallow it,

And he forced in the imhullu-wind so that she could not close her lips.

Fierce winds distended her belly;

Her insides were constipated and she stretched her mouth wide.

He shot an arrow which pierced her belly,

Split her down the middle and slit her heart,

Vanquished her and extinguished her life.

The epic of Enuma Elish reflects the political and religious ideology of Babylon, where Marduk was revered as the supreme god and protector of the city. Marduk represents the ideal king who establishes his sovereignty by defeating his enemies and creating order out of chaos. Tiamat represents the forces of chaos and violence that oppose Marduk’s rule and threaten to undo his creation. The Tablet of Destinies symbolizes the source of legitimate authority and power that belongs to Marduk and his chosen representatives. The epic also expresses the importance of skill, strength, and justice as virtues that enable Marduk to overcome Tiamat.

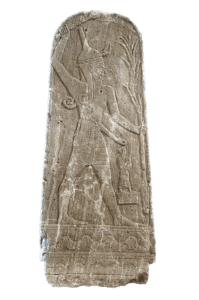

Baal vs Mot

A third example of the combat myth is the Ugaritic epic of Baal and Mot, dating back to the second millennium BCE. The story tells how Baal, the storm god and king of the Canaanite pantheon, struggles to assert his authority over Mot, the god of death and sterility. Baal built a palace on Mount Zaphon as a sign of his kingship and celebrated with a feast. He invites all the gods except Mot, who is offended by his exclusion and challenges Baal to a duel.

Baal is afraid of Mot and tries to avoid the confrontation, but eventually, he agrees to face him. Baal descends to the underworld and fights Mot, but he is defeated and swallowed by him. Baal’s death causes a drought and famine on earth, as his sister Anat, the goddess of war and love, mourns for him. She searches for his body and finds it in the underworld. She confronts Mot and cuts him into pieces, scattering them over the land.

She seized El’s son, Mot.

– Baal Cycle (ANET 140)

With a sword she sliced him;

With a sieve she winnowed him;

With a fire she burnt him;

With millstones she ground him;

In the field she scattered him.

Anat then revives Baal and brings him back to life. Baal returns to his palace and resumes his kingship. He also challenges Mot again, this time with the help of the sun goddess Shapash. He defeats Mot and restores fertility and rain to the earth.

The epic of Baal and Mot reflects the agricultural and seasonal cycle of Canaan, where Baal was worshiped as the god of rain and fertility. Baal represents the life-giving forces of nature that sustain the crops and animals. Mot represents the death-dealing forces of nature that cause drought and barrenness. The epic also expresses the importance of courage, loyalty, and renewal as virtues that enable Baal to overcome Mot.

Yahweh vs. the Sea

A fourth example of the combat myth is the biblical tradition of Yahweh and the Sea, dating back to the first millennium BCE. The story tells how Yahweh, the God of Israel and Judah, asserts his sovereignty over the Sea, a symbol of chaos and evil. The Sea is sometimes identified with other names, such as Leviathan, Rahab, or Dragon. The story has several versions and variations in different biblical texts, such as Genesis 1, Psalm 74 and 89, Isaiah 51, Job 41, and Ezekiel 32. The story usually depicts Yahweh as the creator and ruler of the cosmos, who subdues the Sea and its allies with his power and wisdom.

Yet God is my King from long ago,

– Psalm 74:12-17 (NASB)

Who performs acts of salvation in the midst of the earth.

You divided the sea by Your strength;

You broke the heads of the sea monsters in the waters.

You crushed the heads of [e]Leviathan;

You gave him as food for the creatures of the wilderness.

You broke open springs and torrents;

You dried up ever-flowing streams.

Yours is the day, Yours also is the night;

You have prepared the light and the sun.

You have established all the boundaries of the earth;

You have created summer and winter.

Yahweh also delivers his people from their enemies, such as Egypt, Babylon, or Assyria, who are associated with the Sea and its monsters. Yahweh promises to destroy the Sea and its creatures once and for all in the future when he will establish his eternal kingdom of peace and justice.

Our fathers in Egypt did not understand Your wonders;

– Ps 106:7–12 (NASB)

They did not remember Your abundant kindnesses,

But rebelled by the sea, at the Red Sea.

Nevertheless He saved them for the sake of His name,

So that He might make His power known.

So He rebuked the Red Sea and it dried up,

And He led them through the mighty waters, as through the wilderness.

So He saved them from the hand of one who hated them,

And redeemed them from the hand of the enemy.

The waters covered their adversaries;

Not one of them was left.

Then they believed His words;

They sang His praise.

The biblical tradition of Yahweh and the Sea reflects the historical and theological experience of Israel and Judah, where Yahweh was worshiped as the only true God and the protector of his covenant people. Yahweh represents the supreme God who establishes his authority by defeating his adversaries and saving his people. The Sea represents the forces of chaos and evil that oppose Yahweh’s will and threaten to undo his creation. The biblical tradition also expresses the importance of faith, hope, and obedience as virtues that enable Yahweh’s people to overcome the Sea.

Similarities and Differences between the Combat Myths

The four narratives of the combat myth that we have examined share some common features and themes, but also show some distinctive variations and adaptations.

Similarities:

- All four narratives depict a cosmic conflict between a heroic god and a monstrous enemy, who represent the forces of order and chaos, respectively. The conflict is often related to the creation of the cosmos and the establishment of divine authority.

- All four narratives involve the use of a special weapon or device that enables the heroic god to defeat his enemy. The weapon or device is often associated with the power of wind, storm, or thunder. For example, Ninurta uses the Sharur, Marduk uses the wind weapon, Baal uses thunderbolts, and Yahweh uses his breath or voice.

- All four narratives have a political and ideological dimension, as they reflect and promote the interests and values of their respective cultures and communities. For example, Ninurta and Marduk represent the ideal kings of Mesopotamia, Baal represents the life-giving forces of Canaan, and Yahweh represents the only true God of Israel and Judah.

- All four narratives also have a historical and theological dimension, as they interpret and respond to the events and challenges that their respective cultures and communities faced. For example, Ninurta and Marduk address the threat of chaos and rebellion, Baal addresses the threat of drought and famine, and Yahweh addresses the threat of exile and oppression.

Differences:

- The four narratives differ in their characterization of the heroic god and his enemy. For example, Ninurta and Marduk are both sons of Enlil, but Ninurta is more loyal and obedient to his father, while Marduk is more ambitious and independent. Baal is more human-like and vulnerable than the other gods, as he experiences fear, grief, and death. Yahweh is more transcendent and unique than the other gods, as he has no rivals or equals.

- The four narratives also differ in their characterization of the monstrous enemy. For example, Anzu is a bird-like creature who steals the Tablet of Destinies from Enlil, Tiamat is a dragon-like goddess who creates an army of monsters from her body, Mot is a god of death who swallows Baal into his mouth, and the Sea is a symbol of chaos that opposes Yahweh’s creation and salvation.

- The four narratives also differ in their outcome and implications of the combat myth. For example, Ninurta’s victory leads to his recognition as the king of the gods and his dominion over the mountains, Marduk’s victory leads to his creation of humans as his slaves and worshipers, Baal’s victory leads to his restoration of fertility and rain to the earth, and Yahweh’s victory leads to his deliverance of his people from their enemies.

In conclusion, the combat myth shows how different cultures and communities understood and expressed their worldviews. It depicts a cosmic battle between a heroic god and a monstrous enemy, often representing order and chaos. And it influenced the biblical tradition, especially its view of God and creation.

References:

- Ballentine, Debra Scoggins. The Conflict Myth and the Biblical Tradition. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Black, Jeremy A., et al. Gods, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. Published by British Museum Press for the Trustees of the British Museum, 1992.

- Dalley, Stephanie, translator. “Anzu.” Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 205-222.

- Day, John. God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea: Echoes of a Canaanite Myth in the Old Testament. Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Forsyth, Neil. The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth. United States, Princeton University Press, 2020.

- Horry, Ruth A., and Eleanor Robson. “Anzu the Monstrous Lion-Eagle.” Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project, 2015.

- New American Standard Bible. Updated Edition, The Lockman Foundation, 2020

- Pritchard, James Bennett, editor. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating To The Old Testament. 3. ed. with suppl., 5. printing, Princeton Univ. Press, 1992.

- Tinney, Steve. “Great Beasts of Legend: Anzu the Lion-Headed Eagle.” YouTube, uploaded by Penn Museum, 3 Nov. 2016.

Notes:

- Image Modified: Removed black background. ↩︎

Assyrian & Babylonian Demonology: Evil Spirits in Ancient Mesopotamia

Assyrian & Babylonian Demonology: Evil Spirits in Ancient Mesopotamia