The origins and evolution of Halloween in America are rooted in the ancient festival of the dead called Samhain, celebrated by the Celts. Over the centuries, this pagan tradition was influenced by various cultural and religious practices, such as Christianity, immigration, and commercialization. Today, Halloween in America is a popular and widely celebrated holiday that features costumes, candy, and horror movies.

Samhain: The Celtic Prelude

Long before goblins and witches started knocking on American doors, the Celts in what is now Ireland, the UK, and northern France, honored the festival of Samhain (pronounced “SOW-in” or “SAH-win”). Signaling the end of the harvest and welcoming the chilling embrace of winter, it represented a time when the veil between our world and that of the spirits thinned.

, the eve of the Celtic New Year. On this night, people would gather around huge bonfires, where they would burn crops and animals as offerings to the Celtic gods and goddesses. They would also wear costumes made of animal skins and heads, and tell each other’s fortunes. They believed that wearing these disguises would protect them from being harmed or kidnapped by the fairies and other supernatural beings that roamed the land. Some of these creatures were associated with Samhain, such as the shape-shifting Pukah, the headless horseman Dullahan, and Lady Gwyn, a ghostly woman who chased night wanderers.

After the bonfire ritual, people would return to their homes with a flame from the communal fire, which they would use to relight their hearth fires. This was believed to bring them good luck and protection for the coming winter. They would also leave food and drink outside their doors for the spirits of their ancestors, who were thought to visit them on Samhain night.

The Christianization of Samhain

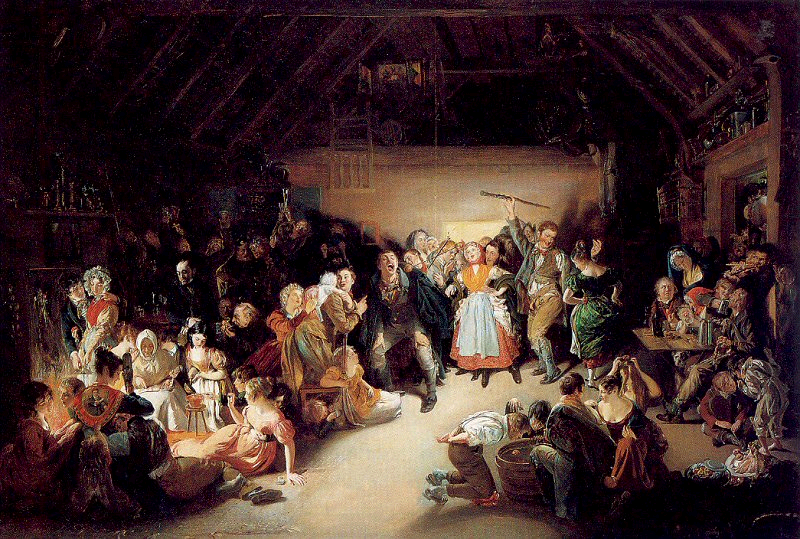

As Christianity spread throughout Europe, it assimilated many pagan festivals and traditions into its own calendar. In the 7th century CE, Pope Gregory III declared November 1 as All Saints’ Day, a day to honor all the Christian martyrs and saints. The night before All Saints’ Day was called All Hallows’ Eve, which later became Halloween. Some scholars believe that this was an attempt by the church to replace Samhain with a more acceptable celebration. However, many of the old Celtic customs and beliefs persisted, especially in Ireland and Scotland, where Samhain was still observed with bonfires, costumes, and divination games. Some of these games involved apples, which were a symbol of Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees. For example, people would bob for apples in a tub of water or peel an apple in one long strip and throw it over their shoulder to reveal the initial of their future spouse.

However, many of the old Celtic customs and beliefs persisted, especially in Ireland and Scotland, where Samhain was still observed with bonfires, costumes, and divination games. Some of these games involved apples, which were a symbol of Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and trees. For example, people would bob for apples in a tub of water or peel an apple in one long strip and throw it over their shoulder to reveal the initial of their future spouse.

Another popular game was called “dumb supper,” in which young women would set a table with food and drink for two, but only one person would sit down to eat. The other chair was reserved for the spirit of their future husband, who would appear if they remained silent throughout the meal. Alternatively, some young women would sit in a dark room with a mirror and a candle, hoping to see the face of their future husband or a skull indicating that they would die before marriage.

A New Home: Halloween in America

Halloween was not widely celebrated in colonial America, where most of the settlers were Puritans or other Protestant denominations that disapproved of such superstitions. However, in some regions where there was more cultural diversity, such as Maryland and the southern colonies, Halloween festivities were more common. These often involved stories of ghosts and witchcraft, as well as dancing and fortune-telling.

The mass immigration of Irish and Scottish people to America in the 19th century brought Halloween to a wider audience. They introduced many of their traditions, such as carving jack-o’-lanterns out of turnips or pumpkins (a practice that originated from an Irish legend about a man named Jack who tricked the devil and was doomed to wander the earth with a lantern), wearing costumes and masks (which were originally intended to fool evil spirits but later became a way to disguise oneself from neighbors), and going door-to-door asking for food or money (a custom that evolved from the medieval practice of “souling,” in which poor people would beg for soul cakes in exchange for prayers for the dead).

Halloween in America became a more secular and community-oriented holiday by the late 19th century, with festive activities for children and adults. The holiday’s scary and superstitious aspects were toned down or replaced by more humorous and whimsical elements. However, some people still used Halloween in America as an excuse to cause mischief and vandalism, which became a serious problem in the 1920s and 1930s.

To prevent such trouble, some communities and organizations promoted the idea of “trick-or-treat,” in which children would go from house to house and receive candy or other treats in return for not playing pranks. This practice became widely popular after World War II when sugar rationing ended and candy manufacturers began to market their products for Halloween. Trick-or-treating also reflected the postwar baby boom and suburbanization of America, as it encouraged social interaction and integration among neighbors.

Halloween in Modern America

Today, Halloween is one of the most commercialized and widely celebrated holidays in America, with an estimated $9 billion spent on costumes, decorations, candy, and other items every year. It is also a highly creative and expressive holiday, as people of all ages enjoy dressing up, carving pumpkins, watching horror movies, visiting haunted attractions, and throwing parties. Halloween has also become more multicultural and inclusive, as people from different backgrounds and traditions share their own ways of celebrating the occasion.

However, Halloween is not without controversy or criticism. Some religious groups, such as conservative Christians and Jehovah’s Witnesses, denounce Halloween as a pagan or satanic holiday that should be avoided. Some parents and educators are concerned about the safety and health of children who participate in trick-or-treating or consume too much candy. Some activists and scholars are critical of the cultural appropriation and stereotyping that often occur in Halloween costumes and media representations. And some environmentalists and animal rights advocates are opposed to the waste and cruelty that are associated with some Halloween practices.

Yet, Halloween’s enduring charm lies in its dynamic nature, reflecting the vast diversity of the American cultural landscape. Whether seen as a night of fun or a bridge to ancient traditions, it stands as a mirror, reflecting society’s evolving beliefs, fears, and aspirations.

References

- History.com Editors. (2021). History of Halloween.

- Britannica Editors. (2020). Samhain.

- Rogers, N. (2002). Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford University Press.

- Santino, J. (Ed.). (1994). Halloween and Other Festivals of Death and Life. University of Tennessee Press.

- Skal, D.J. (2002). Death Makes a Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween. Bloomsbury.

The Ascension of Jesus: From Earthly Mysteries to Heavenly Revelations

The Ascension of Jesus: From Earthly Mysteries to Heavenly Revelations