In 1853, in the heart of ancient Nineveh, now known as Mosul in Iraq, a remarkable discovery lay in wait. English archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard, with the assistance of his Iraqi counterpart Hormuzd Rassam, uncovered an ancient library of the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal. Among the myriad tablets inscribed with cuneiform, one narrative stood out: the Epic of Gilgamesh. But what makes a 4,000-year-old text from a Mesopotamian king’s collection significant to the modern world?

Epid of Gilgamesh: History and Myth

First translated by George Smith from the British Museum in 1872, The Epic of Gilgamesh recounts the exploits of its titular king and his search for immortality. Emerging from ancient Mesopotamia, situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, this poem delves deeper than heroic adventures and divine rendezvous—it deeply probes the human psyche, exploring friendship, grief, and the unrelenting passage of time.

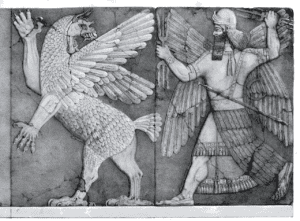

This venerable text depicts Gilgamesh’s metamorphosis from a tyrannical leader to a wise king. Gilgamesh and Enkidu become friends after a fierce initial combat. Their bond grows as they embark on adventures, including the slaying of the Bull of Heaven, which was sent by the goddess Ishtar as punishment for Gilgamesh’s arrogance.

However, after Enkidu dies by divine decree, Gilgamesh embarks on a profound quest for understanding and immortality.

Gilgamesh was not only a literary protagonist but also a historical figure. He was reputedly the fifth king of Uruk, a city-state in southern Mesopotamia that is now modern Warka in central Iraq. He is associated with the city’s legendary walls and temples. He is also mentioned in a list of Sumerian kings that chronicles the rulers of ancient Mesopotamia. According to this list, Gilgamesh reigned for 126 years and his father was either Lugalbanda, a previous king of Uruk, or a lillu, a type of vampire-like spirit.

Gilgamesh’s exploits were also recorded in various Sumerian stories that predate the Epic of Gilgamesh. These stories include:

- Gilgamesh and the Halub-Tree: Gilgamesh travels to a forest to cut down a sacred tree that is guarded by a serpent. He defeats the serpent and brings back the tree to Uruk.

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa: Gilgamesh and Enkidu journey to the Cedar Forest to confront Huwawa, a monstrous guardian appointed by Enlil, the god of wind and storms. They kill Huwawa and cut down the cedar trees.

- Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven: Gilgamesh rejects the advances of Ishtar, the goddess of love and war. She sends the Bull of Heaven to wreak havoc on Uruk. Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the bull and insult Ishtar.

- The Death of Gilgamesh: Gilgamesh falls ill after having a dream that foreshadows his death. He dies and is mourned by his people.

- The Flood: Utnapishtim tells Gilgamesh how he survived a great flood that wiped out humanity. He was instructed by Ea, the god of wisdom and water, to build a boat and save his family and animals. After the flood subsided, he was granted immortality by Enlil.

- The Descent of Inanna/Ishtar: Inanna/Ishtar descends to the underworld to visit her sister Ereshkigal, the queen of the dead. She is stripped of her clothes and jewels and killed by Ereshkigal’s judges. She is revived by two creatures sent by Ea and returns to the upper world.

- Gilgamesh and Agga: Gilgamesh refuses to pay tribute to Agga, the king of Kish. He challenges Agga to a battle and defeats him.

The Evolution of the Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is not a singular tale but a compilation of various narratives that reflect different periods and cultures in Mesopotamian history. The earliest version of the Epic dates back to the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000-1600 BCE). It was found in fragments at various sites, such as Ur, Nippur, Megiddo, and Tell Harmal. It consists of four tablets that contain stories such as Gilgamesh and Huwawa, Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, The Death of Gilgamesh, and The Flood.

The most complete version of the Epic dates back to the Neo-Assyrian period (ca. 911-612 BCE). It was found in Ashurbanipal’s library at Nineveh. It consists of twelve tablets that contain stories such as Gilgamesh and Enkidu, The Cedar Forest, The Death of Enkidu, The Search for Immortality, The Return of Gilgamesh, and The Death of Gilgamesh. It also includes a prologue and an epilogue that frame the story as a royal inscription.

The differences between the Old Babylonian and the Neo-Assyrian versions reflect the changing political and religious contexts of Mesopotamia. For example, the Old Babylonian version emphasizes Gilgamesh’s heroic deeds and divine ancestry, while the Neo-Assyrian version emphasizes his human limitations and moral lessons. The Old Babylonian version portrays Enkidu as a wild man who is civilized by a prostitute, while the Neo-Assyrian version portrays him as a noble savage who is created by the gods. The Old Babylonian version depicts Ishtar as a vengeful goddess who is spurned by Gilgamesh, while the Neo-Assyrian version depicts her as a compassionate goddess who intervenes on behalf of Gilgamesh.

The Significance of the Epic of Gilgamesh

Since its rediscovery, the Epic of Gilgamesh has influenced and inspired scholars, writers, and artists from various fields and backgrounds. It has also challenged and enriched our understanding of ancient Mesopotamia and its connections with other civilizations.

For instance, it shed light on our understanding of Kingship in Ancient Mesopotamia. Kingship was seen as a divine mandate that required the king to uphold justice, maintain order, protect the weak, and ensure prosperity. Kingship also involved a close relationship between the king and the gods, who could grant or withdraw their favor depending on the king’s actions. The Epic of Gilgamesh shows how Gilgamesh learns to balance his divine and human aspects, his personal desires and public duties, his pride and humility, and his mortality and legacy.

It is also considered one of the earliest examples of epic poetry, a genre that includes works such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, and Dante’s Divine Comedy. Epic poetry is characterized by its long narrative form, its use of elevated language and style, its invocation of divine or supernatural forces, its depiction of heroic deeds and journeys, and its reflection of cultural values and ideals.

In conclusion, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a remarkable work of literature that has survived for millennia and continues to fascinate and inspire us today. It is not only a historical document that reveals the culture and worldview of ancient Mesopotamia, but also a timeless story that explores the universal themes of friendship, mortality, and the meaning of life. It is also a testament to the power of textual archaeology, which can uncover the layers of myth and history that shape our collective imagination. The Epic of Gilgamesh invites us to reflect on our own humanity and our place in the world.

References

- Dalley, Stephanie, editor. Myths From Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Rev. ed, Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Forsyth, Neil. The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth. Princeton University Press, 1987.

- Heidel, Alexander. The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels. 7th impr, University of Chicago Press, 1970.

- Tigay, Jeffrey H. The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Bolchazy-Carducci, 2002.

How Ancient Myths Shape Our Modern World

How Ancient Myths Shape Our Modern World