In the year 1582, a mysterious man named Edward Kelley arrived at the home of John Dee, a renowned scholar and astrologer in England. Kelley claimed to have a gift of communicating with angels and offered to help Dee in his quest for divine knowledge. Dee, who had been studying the ancient writings of Hermes Trismegistus, Zoroaster, and other occult philosophers, eagerly accepted Kelley’s offer. Together, they embarked on a series of magical experiments that involved scrying, alchemy, and angelic conversations. Their adventures would take them across Europe, from Poland to Bohemia, where they would encounter kings, emperors, and mystics.

Dee and Kelley were not alone in their fascination with occult philosophy. During the 15th and 16th centuries, Europe witnessed a revival of interest in esoteric studies, as scholars sought to recover the lost wisdom of the ancients. Occult philosophy was a term that encompassed a variety of topics, such as astrology, numerology, cabala, alchemy, magic, and natural philosophy. These topics were not seen as separate from religion or science, but rather as complementary ways of understanding the nature of God and the universe.

The Origins of Occult Philosophy

Occult philosophy drew from a rich and diverse source of influences, both ancient and medieval. It was based on the idea that there is hidden or esoteric knowledge that can be revealed to the initiated through various methods and practices. Some of the main influences on occult philosophy were:

- Hermeticism – a tradition that originated from the writings attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, a mythical figure who was considered to be the founder of alchemy, astrology, and magic. Hermeticism combined elements of Egyptian, Greek, and Jewish thought, and taught that the universe is governed by the principle of correspondence: “As above, so below; as within, so without”.

- Cabala – a mystical interpretation of the Hebrew scriptures that developed in medieval Jewish communities. Cabala explored the hidden meanings of the letters, numbers, and names of God, and sought to achieve a direct connection with the divine through meditation, prayer, and ritual. Cabala also influenced Christian and Islamic mystics, who adapted its concepts and symbols to their own faiths.

- Ancient philosophy – especially the schools of Platonism and Neoplatonism, which emphasized the existence of a transcendent reality beyond the material world. Platonism and Neoplatonism also introduced the concept of the One, the Good, or the First Principle, from which all things emanate and to which all things return. These ideas inspired many occult philosophers to seek the unity of all things and the ultimate source of wisdom.

Occult philosophy in the Elizabethan age was a synthesis of various sources of ancient and medieval wisdom that sought to uncover the hidden secrets of nature and God. By using different methods and practices, such as hermeticism, cabala, alchemy, astrology, and magic, occult philosophers tried to achieve a direct connection with the divine and to transform themselves and the world. Their works reflected the influence of Hermes Trismegistus, the Hebrew scriptures, and the Platonic and Neoplatonic traditions, as well as their own original insights and discoveries.

The Renaissance of Occult Philosophy

The revival of occult philosophy in the 15th and 16th centuries was largely due to the efforts of humanist scholars who sought to recover the original texts and languages of the ancients. They translated and edited many works that had been lost or corrupted over time, such as the Hermetic corpus, the works of Plato and Aristotle, and the writings of Zoroaster. They also collected and studied manuscripts that contained medieval magical treatises, such as those by Roger Bacon and Albertus Magnus.

These scholars, such as Marsilio Ficino, Pico della Mirandola, Henry Cornelius Agrippa, and John Dee used different methods and practices, such as hermeticism, cabala, alchemy, astrology, and angelic magic, to pursue their quest for the ultimate truth. Their works influenced not only the scientific and cultural development of their time but also the later generations of esoteric thinkers and practitioners.

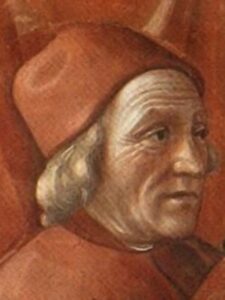

Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499)

Marsilio Ficino was one of the most influential figures of the Renaissance. He was a scholar, philosopher, priest, and astrologer who translated many ancient texts into Latin, including the works of Plato and the Corpus Hermeticum. He founded the Platonic Academy in Florence, where he gathered a circle of intellectuals who shared his interest in Neoplatonism and Hermeticism.

Ficino believed that occult philosophy could harmonize Christianity with classical wisdom, and reveal the hidden unity of all things. He also practiced natural magic, which he defined as “the highest realization of natural philosophy”. He used astrological talismans, musical harmonies, and herbal remedies to heal himself and his friends from physical and mental illnesses.

Ficino also wrote original works on various topics, such as love, magic, astrology, and theology. He composed commentaries on Plato’s Symposium and Plotinus’ Enneads, as well as treatises such as De Amore (On Love), De Vita Libri Tres (Three Books on Life), and Theologia Platonica (Platonic Theology). He also wrote letters, poems, and hymns. He was a prolific and influential writer who shaped the intellectual and cultural landscape of the Renaissance.

Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494)

Pico della Mirandola was another prominent member of the Platonic Academy. He was a prodigy who mastered several languages and disciplines at a young age. He wrote his famous Oration on the Dignity of Man, which celebrated human potential and freedom.

Pico della Mirandola was a Renaissance scholar who synthesized various sources of knowledge, such as Aristotelianism, Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, Cabala, magic, and astrology, into his 900 Theses. He argued that these sources were compatible with Christianity and that they could lead to a universal wisdom that transcended all differences. Using Cabalistic arguments, he tried to convert Jews to Christianity.

Pico della Mirandola faced many challenges and controversies in his life. He had to flee from Rome after Pope Innocent VIII condemned his 900 Theses as heretical and dangerous. He was also kidnapped and imprisoned by his own brother, who disapproved of his lifestyle and associates. He befriended and admired Savonarola, a radical preacher who denounced the corruption and decadence of the Church and the Medici. He died shortly after Savonarola was executed for heresy and sedition.

Henry Cornelius Agrippa (1486-1535)

Henry Cornelius Agrippa was a German polymath who wrote one of the most comprehensive and influential books on occult philosophy: De Occulta Philosophia Libri Tres (Three Books of Occult Philosophy). In this work, he systematized the various branches of occult knowledge according to a threefold structure: natural magic (which dealt with natural phenomena), celestial magic (which dealt with celestial influences), and ceremonial magic (which dealt with spiritual entities). He also discussed topics such as numerology, geomancy, divination, necromancy, witchcraft, and demonology. He argued that occult philosophy was not contrary to reason or religion, but rather a means to understand God’s creation and achieve spiritual perfection.

Agrippa’s life was full of adventures and controversies. He traveled extensively throughout Europe, seeking ancient and esoteric sources of knowledge. He served as a soldier, a physician, a lawyer, and a teacher. He was accused of heresy and witchcraft by the Inquisition and had to flee from several cities. He also had many influential friends and patrons, such as Margaret of Austria, Erasmus of Rotterdam, and King Francis I of France. He died in 1535, leaving behind a legacy of occult wisdom and curiosity.

John Dee (1527-1608)

John Dee was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, alchemist, and spy who served Queen Elizabeth I as her advisor on scientific and political matters. He was also fascinated by occult philosophy, especially by Hermeticism and Cabala. He believed that he could discover the secrets of nature and history by deciphering a primordial language that God used to create the world: the Enochian language.

He conducted a series of scrying sessions with his assistant Edward Kelley, who claimed to see visions of angels in a crystal ball. Dee recorded these visions in his diaries, which contained complex diagrams, symbols, and words in Enochian. He hoped that by communicating with the angels, he could obtain divine guidance for himself and for England.

Dee’s interest in the occult led him to seek contact with the spiritual realm, which he believed was the source of all knowledge. He experimented with various methods of scrying, such as using a crystal ball, a black mirror, or a bowl of water. He also studied the writings of ancient mystics, such as Hermes Trismegistus, Enoch, and Zoroaster, to learn the secrets of creation, prophecy, and immortality from these sources.

These enigmatic figures, with their daring quests and revolutionary ideas, stood at the crossroads of reason and revelation. Their audacity to chart unknown realms and challenge the boundaries of knowledge transformed the esoteric from mere mysticism into a robust philosophical field, laying the groundwork for centuries of exploration.

The Legacy of Occult Philosophy

Occult philosophy had a significant impact on the intellectual and cultural history of Europe. It inspired many artists, writers, musicians, scientists, and explorers to pursue their creative and innovative endeavors. It also challenged some of the established authorities and dogmas of the church and state. It provoked controversies and debates among theologians,

philosophers, and magistrates. It also attracted accusations and persecutions from those who feared or opposed its teachings.

Occult philosophy also had a lasting influence on the development of modern esoteric movements, such as Rosicrucianism, Freemasonry, Theosophy, and New Age Thought. Many of these movements adopted and adapted some of the ideas and practices of occult philosophy, such as the concept of the microcosm and the macrocosm, the doctrine of correspondences, the use of symbols and rituals, and the quest for spiritual enlightenment.

Occult philosophy was a fascinating and complex phenomenon that reflected the spirit of the Renaissance. It was a synthesis of ancient and medieval wisdom, a celebration of human potential, and a search for divine truth. It was a renaissance of magic.

Reference

- Copenhaver, B.P. “Renaissance Magic and Neoplatonic Philosophy: Ennead 4.3-5 in Ficino’s De vita coelitus comparanda.” Marsilio Ficino e il ritorno di Platone, edited by G.C. Garfagnini, vol. 2, Florence, 1986, pp. 351-381.

- Lehrich, Christopher I. The Language of Demons and Angels: Cornelius Agrippa’s Occult Philosophy. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

- Rabin, Sheila J. “Pico on Magic and Astrology.” Pico Della Mirandola: New Essays, edited by M. V. Dougherty, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007, pp. 152–178.

- Sherman, William H. John Dee: The Politics of Reading and Writing in the English Renaissance. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1995.

- Walker, D.P. Spiritual and Demonic Magic from Ficino to Campanella. London: Warburg Institute, 1958.

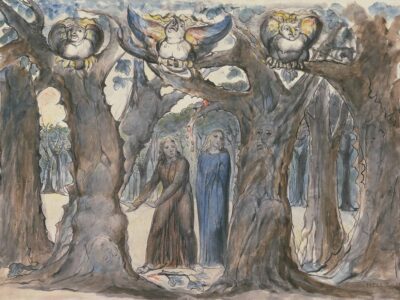

Lilith, Samael, and Asmodeus: The Triad of Evil in Lurianic Kabbalah

Lilith, Samael, and Asmodeus: The Triad of Evil in Lurianic Kabbalah