Author: John J. Collins

Publisher: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Year Published: 1998

The Apocalyptic Imagination is absolutely essential for anyone interested in early Apocalyptic literature. This book is a thorough introduction to literature such as Daniel, 1 and 2 Enoch, and 3 Baruch, 4 Ezra, Revelation, the Sibylline Oracles, the Apocalypse of Abraham, and the Testament of Abraham.

Collins begins his book by addressing the apocalyptic genre in an attempt to define writings that may be labeled ‘apocalyptic’. The major works we define in the ‘apocalypse’ literature were not described as such in antiquity. The word comes from the Greek “apokalypsis” meaning revelation and was not used before Christianity, where is introduced what we know as the last book of the Bible, Revelation. ‘Apocalypticism’ is used to mean a historical movement or to refer ‘to the symbolic universe in which an apocalyptic movement codifies its identity and interpretation of reality.’ A movement then would be called ‘apocalyptic’ if it ‘shared the conceptual framework of the genre, endorsing a worldview in which supernatural revelation, the heavenly world, and eschatological judgment played essential parts.’

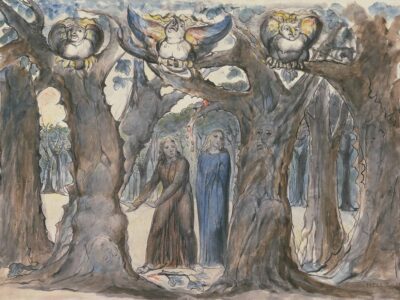

The general framework of an apocalypse describes some kind of revelation being transmitted by a vision or otherworldly journey. The seer usually engages in dialogue with an otherworldly being or is allowed to read a heavenly book. There is almost always an angel that acts as an interpreter of the vision or serves as a guide during the journey, implying that the revelation requires some kind of otherworldly aid to be interpreted correctly. The seer almost always pseudonymously takes the name of a figure from the past. Apocalypses are broken down into 2 categories: the historical apocalypses – such as Daniel, 4 Ezra, Jubilees, Apoc of Weeks, Animal Apocalypse and the otherworldly – such as 3 Baruch, 2 Enoch, Similitudes, Astronomical Book, 1 Enoch 1-36

Collins next addresses the early Enoch Literature, specifically the 5 separate compositions that make up 1 Enoch: the Book of the Watchers (chaps 1-36), the Similitudes (chaps 37-71), the Astronomical Book (chaps 72-82), the Book of Dreams (chaps 83-90), and the Epistle of Enoch (chaps 91-108). The historical figure of Enoch is addressed in Genesis 5:18-24, ‘Thus, all the days of Enoch were three hundred and sixty-five years. Enoch walked with God and he was not, for God took him.’

After a lengthy treatise on the background and interpretation of 1 Enoch, Collins moves on to the book of Daniel, the only example of apocalyptic literature in the Hebrew Bible. Daniel was written in the time of Antiochus Epiphanes, an argument formulated as early as the 3rd century by the neo-Platonic philosopher, Porphyry. Porphyry proposed that since Daniel ‘predicted’ the course of events up to the time of Antiochus Epiphanes but not beyond it, it could not be dated during the Babylonian exile. Scholars universally accept that prophecies took place ‘after the fact.’ Collins continues with explanations of the dream of the four kingdoms in Daniel 2, the ‘one like the son of man’ vision and ‘the holy ones of the Most High shall receive the kingdom and possess the kingdom forever’ passage in Daniel 7, and the revelation of Daniel 10-12.

A discussion of the Oracles and Testaments follows. Here, Collins presents the Sibylline Oracles within their Hellenistic background and describes key passages from them. A sibyl was usually an ecstatic woman who uttered prophecies. The Testament literature, on the other hand, were discourses delivered as one awaited imminent death, and the literature typically took the form of a father addressing his sons or a leader addressing his people. Some of the prominent Testaments addressed are the Testament of Moses (early 1st century CE) and the Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs.

Qumran is discussed briefly in this book, as Collins has devoted an entire book to the apocalypticism in the Dead Sea Scrolls. This chapter gives more of a history of the Qumran sect and some of their fundamental beliefs such as dualism particularly between light and darkness, the periods of history, their messianic expectation and belief in two messiahs, and finally, the afterlife.

After a brief chapter on the Similitudes of Enoch, Collins addresses some of the literature that arose after the fall of the Second Temple in 70 CE. Of particular interest are 4 Ezra and 2 Baruch, which describe the fall of the Temple in allegory form as the destruction at the hands of the Babylonians. A third text, the Apocalypse of Abraham, also written around this time, is a supernatural revelation on the history of the world and concerns questions of evil and the chosen people. Azazel plays the main character that has dominion over those who do evil.

Chapter 8 discusses the apocalyptic literature from the Diaspora in the Roman Period. Here, again, the Sibylline Oracles are discussed as well as 2 Enoch, 3 Baruch, and the Testament of Abraham.

The final chapter addresses apocalypticism in early Christianity including a discussion on Jesus as an eschatological prophet and the son of man and messiah titles. There is a brief discourse on Paul’s eschatology, and finally, Revelation is discussed.

This book is a must-read for anyone looking for a background in apocalyptic literature. Collins provides an easy to follow framework with lots of textual references to back up his conclusions.