If you’ve read any of the other postings about voodoo dolls or curse tablets, you may be wondering, did it ‘work’? The most common explanation is that yes, it did ‘work,’ but it worked through shared belief – the spell caster believed the spell would work on the victim, while the victim feared that the spell would come true. As the victim became more paranoid, he/she attributed physical/emotional problems directly to the curse. Plato offered a similar explanation:

Another kind of witchcraft (pharmakeia) with its so-called sorceries, charms and binding-spells persuades those attempting to harm their victims that they really are able to achieve such a thing, and persuades their victims that, more than anything, they are being harmed by those who are able to work magic. (Plato, Laws 933a)

For example, in the case of prayer for justice curse, the wrongdoer’s sense of guilt for committing the crime may induce some type of illness or mental anguish which he attributes to his sense of guilt and thus starts him on a downward spiral. An innocent person, however, would not have reason to feel guilty, and therefore a curse would be less likely to work on him.

Widespread Belief in Magic in the 1st Century

In any case, writers of the time wrote of the widespread belief in magic. Pliny asserted that everyone feared curse tablets (Natural History 28.4.19) However, it is probable that most magical practices were done in secret, with many texts instructing its reader not to tell anyone about this – so why did everyone believe this and how would it have had the effects it did? Additionally, in all probability, harmful magical practice was illegal, though magic was probably not banned altogether. While Classical Greece did not have a formal law banning binding spells, they may have been covered under the ‘harmful pharmaka‘ code from Teos of 479 BEC. There was also the crime of impiety in classical Athens that may also have caught harmful magical practices. Plato outlaws binding spells in his hypothetical Laws (933a). Rome had outlawed harmful magic from the time of the Twelve Tables in the 5th century BCE (Apuleius, Apology 47) among a number of other possible laws.

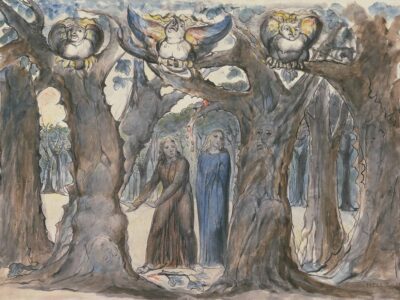

Voodoo Dolls

Perhaps Plato’s reference to people being frightened by wax voodoo dolls fixed at the meeting points of three roads, their parents’ tombs, or on their doors provides some explanation. The displayed doll’s purpose may have been to inform the victim that a curse had been placed upon him, and he would then be subject to his own powers of suggestion. The spell caster would remain anonymous, but he would have let his victim know, quite graphically, that he was now the victim of a curse. It is also possible that some prayers for justice were nailed up for display, as they weren’t considered ‘harmful’ and therefore illegal. Additionally, the casting of the spell may have put its curser at ease, having finally done something, about his situation. Perhaps it was beneficial to his own mental well being.

Reference

- Ogden, Daniel. “Binding Spells: Curse Tablets and Voodoo Dolls in the Greek and Roman Worlds.” Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: Ancient Greece and Rome. University of Pennsylvania Press (November 1999) ISBN: 0812217055

Greco-Roman Curses: Curse Tablets

Greco-Roman Curses: Curse Tablets