Genesis and Enuma Elish are two ancient creation stories that reveal how the ancient Israelites and their neighbors understood the origin of the world and humanity. The book of Genesis, the first book of the Hebrew Bible, contains not one, but two different accounts of how God created everything. These stories have fascinated scholars and believers for centuries, as they show the beliefs and values of the ancient Israelites, as well as their interaction with other cultures and religions.

This essay examines the similarities and differences between Genesis and Enuma Elish, exploring how they express different views on God, the world, and humanity. The essay will also analyze the possible sources and influences of these stories, as well as their importance for understanding the ancient cultures and religions that shaped them.

Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

- Genesis: Dual Narratives of Creation

- Enuma Elish: Babylon’s Origin Myth

- Creation in Context: Parallels Between Genesis and Enuma Elish

- Distinctive Worldviews: Differences Between Genesis and Enuma Elish

- Ancient Echoes: Common Motifs in Near Eastern Myths

- Theological Insights from Genesis’ Second Account

- Complementary Visions: Harmonizing Genesis’ Creation Tales

Genesis: Dual Narratives of Creation

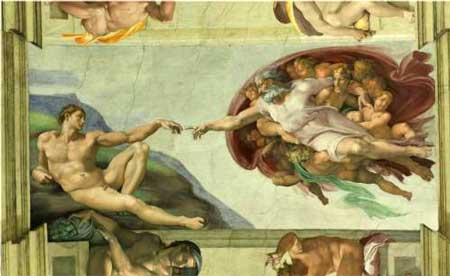

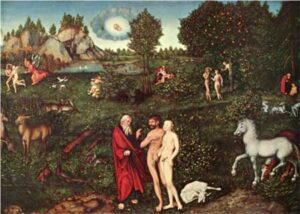

The first creation story (Genesis 1:1-2:3) is a majestic and orderly account of how God spoke the world into existence in six days and rested on the seventh. The second creation story (Genesis 2:4-3:24) is a more intimate and human-centered account of how God formed the first man from the dust, planted a garden for him, and then made a woman from his rib. The second story also includes the famous episode of the serpent tempting Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, leading to the fall of humanity and their expulsion from paradise.

Why are there two different creation stories in Genesis? How do they relate to each other and to other ancient Near Eastern myths? What do they tell us about the nature of God, humanity, and evil? These are some of the questions that this article will explore, by comparing and contrasting the two Genesis creation stories with an earlier Babylonian creation myth, the Enuma Elish.

Enuma Elish: Babylon’s Origin Myth

The Enuma Elish is a Babylonian epic poem that dates back to around 1900-1600 BCE. It was written in Akkadian, the language of ancient Mesopotamia, and inscribed on seven clay tablets. These tablets were discovered in the ruins of the library of Ashurbanipal, the last great king of Assyria, in Nineveh.

In this epic poem, Marduk becomes the supreme ruler of the universe after defeating the primordial goddess Tiamat and her army of chaos. Marduk then created the world from Tiamat’s body, dividing it into heaven and earth. He also established the order of the cosmos, assigning roles and duties to the other gods. He then created human beings from the blood of Kingu, Tiamat’s consort, to serve and worship the gods.

This epic was also recited during the New Year festival in Babylon, which celebrated the renewal of life and order in spring. The festival also honored Marduk as the king of the gods and the protector of Babylon. The recitation of the epic was meant to reaffirm Marduk’s authority and power over the forces of chaos and evil, as well as to ensure his favor and blessing for the city and its people.

Creation in Context: Parallels Between Genesis and Enuma Elish

Some scholars have suggested that the first creation story in Genesis was influenced by or written in response to the Enuma Elish, as there are some similarities between them. For example:

- Both stories depict a state of chaos or disorder

- Both stories use the word “deep” (tehom in Hebrew, Tiamat in Akkadian) to describe the primordial chaos.

- Both stories have a similar order of creation: light, sky, dry land, celestial bodies, animals, and humans.

- Both stories describe a divine rest after completing the creation.

Distinctive Worldviews: Differences Between Genesis and Enuma Elish

However, there are also significant differences between the two stories, which reflect the different theological and cultural perspectives of their authors. For example:

- The Enuma Elish is polytheistic, while Genesis is monotheistic. There is only one God in Genesis, who creates by his word alone, while there are many gods in the Enuma Elish, who create by fighting and killing each other.

- The Enuma Elish is mythological, while Genesis is demythologized. Genesis avoids using words that could be associated with other gods or natural forces, such as sun (shemesh), moon (yareach), sea (yam), etc., and instead uses generic terms such as light (or), sky (raqia), water (mayim), etc. The Enuma Elish uses vivid imagery and symbolism to describe the cosmic battle between Marduk and Tiamat.

- The Enuma Elish is conflictual, while Genesis is peaceful. Genesis portrays God as sovereign and unopposed in his creation. The Enuma Elish depicts a violent struggle between opposing forces of order and chaos.

- The Enuma Elish is anthropomorphic, while Genesis is transcendent. Genesis emphasizes God’s difference and distance from his creation. He does not interact directly with humans or animals. The Enuma Elish portrays the gods as having human-like emotions and behaviors, such as anger (Tiamat’s rage), fear (the other gods’ cowardice), and pride (Marduk’s boasting). They also mingle with humans and animals.

- The Enuma Elish is hierarchical, while Genesis is egalitarian. Genesis affirms that humans are created in God’s image and likeness, male and female equally. They are given dominion over the earth and its creatures. The Enuma Elish asserts that humans are created from the blood of a slain god, to serve the gods as slaves. They are also divided into classes and genders according to their roles.

Ancient Echoes: Common Motifs in Near Eastern Myths

The second creation story in Genesis shares some common elements with other ancient Near Eastern myths, such as:

- The motif of forming a human from clay or dust. For instance, in the Babylonian epic Enuma Elish, the god Marduk creates humans from the blood of the slain god Kingu. In the Egyptian myth of Khnum, the god of the Nile forms humans on his potter’s wheel from clay. In the Greek myth of Prometheus, the Titan shapes humans from clay and water, and Athena breathes life into them.

- The motif of planting a garden or paradise for humans. For instance, in the Sumerian myth of Dilmun, the god Enki creates a garden paradise for his lover Ninhursag, where they live in harmony with animals and plants. In the Persian myth of Jamshid, the king creates a garden called Pairi-Daeza, where he rules over humans and fairies.

- The motif of a forbidden tree or fruit. For instance, in the Sumerian myth of Inanna and the Huluppu Tree, the goddess Inanna plants a sacred tree in her garden, hoping to make a throne and a bed from its wood. However, she finds that a serpent, a bird, and a demon have taken residence in the tree, and she asks her hero Gilgamesh to help her remove them. In the Greek myth of the Garden of Hesperides, the goddess Hera plants a tree with golden apples that grant immortality. She assigns a dragon named Ladon to guard it, but the hero Heracles manages to steal some apples as part of his twelve labors.

- The motif of a serpent or dragon as an adversary or tempter. For instance, in the Mesopotamian myth of Adapa, the sage Adapa breaks the wing of the south wind and is summoned to heaven by the god Anu. On his way, he meets two guardians who advise him not to eat or drink anything offered by Anu, as they are poisoned. However, Anu is impressed by Adapa’s wisdom and offers him bread and water of life, which would make him immortal. Adapa refuses them, thinking they are deadly, and thus loses his chance to become a god. The guardians are later identified as serpents or dragons. In the Canaanite myth of Baal and Anat, the god Baal battles against a seven-headed dragon named Lotan or Leviathan, who represents chaos and evil. Baal defeats the dragon with the help of his sister Anat, who is also his lover.

Theological Insights from Genesis’ Second Account

However, again, there are also important differences between the second creation story in Genesis and other ancient Near Eastern myths, which show its distinctive theological and ethical message. For example:

- The second creation story in Genesis portrays God as personal and relational. He breathes life into the man, walks with him in the garden, and makes a suitable partner for him. He also cares for the animals and plants that he created.

- The second creation story in Genesis portrays humans as free and responsible. They are given the choice to obey or disobey God’s command. They are also given the task to name and care for the animals and plants. They are accountable for their actions and their consequences.

This second creation story also does not imply any notion of a “fall” or “original sin” as later Christian thinkers such as Paul and Augustine would assert. The Hebrew text does not portray Adam and Eve’s disobedience as a cosmic catastrophe that corrupted human nature and the world. Rather, it shows the consequences of their action as natural and inevitable, such as pain in childbirth, toil in farming, and death. The story also does not blame Eve or the serpent for the sin, but holds both Adam and Eve equally responsible.

Moreover, the story does not depict God as angry or vengeful, but as compassionate and merciful. He clothes them, protects them from eating from the tree of life, and promises them a future offspring who will overcome the serpent. Thus, the second creation story in Genesis offers a more nuanced and realistic view of human nature and God’s relationship with humanity than later theological interpretations.

Complementary Visions: Harmonizing Genesis’ Creation Tales

The two creation stories in Genesis and Enuma Elish offer different perspectives on the origin and meaning of the world and humanity. They reflect the cultural and religious contexts of their authors, as well as their interactions with other ancient Near Eastern myths. They also reveal different aspects of God’s character and relationship with his creation. By comparing and contrasting these stories, we can gain a deeper understanding of the diversity and complexity of the biblical and Babylonian worldviews, as well as their relevance and significance for today.

References

- Alter, Robert. Genesis: Translation and Commentary. W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

- Alter, Robert. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

- Anderson, Gary A. The Genesis of Perfection: Adam and Eve in Jewish and Christian Imagination. Westminster John Knox Press, 2001.

- Collins, John J. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible: Third Edition. Fortress Press, 2018.

- Dalley, Stephanie, editor and translator. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford University Press, 2008

- Mark, Joshua J. “Ancient Persian Mythology.” World History Encyclopedia, 9 Dec. 2019

- Pritchard, James B., editor. The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton University Press, 2011.

- “The Creation – Greek Mythology.” GreekMythology.com

Angels in the Hebrew Bible: From Messengers to Guardians

Angels in the Hebrew Bible: From Messengers to Guardians